This posting is about the challenges of testing applications and building quality in with a solid testing strategy. All good software engineers know that they should be writing units tests, but still due to a number of reasons they don’t do it. Sometimes it is because they just don’t know how to write them, and sometimes it is because they are just damn lazy. They figure that their job is to be a developer and write the code, and it is the testers’ job to find their errors or to develop automation tests for them. Good developers don’t accept that premise. Good developers take pride in their work and collaborated with the testers to create a system that minimizes the probability of defects.

We typically divide tests into 3 categories: unit tests to test at a fine grain, integration tests to test the integration of multiple units, and end-to-end tests which are typically executed via a user interface.

Naresh Jain, posted a nice blog on “Inverting the Testing Pyramid.” Here’s a short summary.

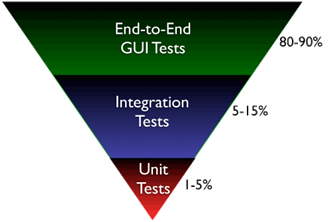

Most software organizations today suffer from what I called the “Inverted Testing Pyramid”. They spend maximum time and effort building end-to-end GUI test. Very little effort is spent on building unit/micro tests. Hence they end up with majority (80-90%) of their tests being end-to-end GUI tests. Some effort is spent on writing so-called “Integration test” (typically 5-15%.) Resulting in a shocking 1-5% of their tests being unit/micro tests.

Why is this a problem?

The base of the pyramid is constructed from end-to-end GUI test, which are famous for their fragility and complexity. A small pixel change in the location of a UI component can result in test failure. GUI tests are also very time-sensitive, sometimes resulting in random failure. To make matters worse, most teams struggle automating their end-to-end tests early on, which results in huge amount of time spent in manual regression testing. It’s quite common to find test teams struggling to catch up with development. This lag causes many other hard-development problems. Number of end-to-end tests required to get a good coverage is much higher and more complex than the number of unit tests + selected end-to-end tests required.

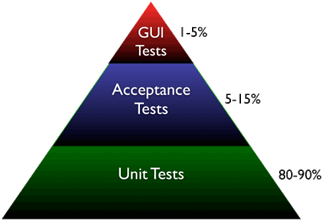

What I propose and help many organizations achieve is the right balance of end-to-end tests, acceptance tests and unit tests. I call this “Inverting the Testing Pyramid.” [Inspired by Jonathan Wilson’s book called Inverting The Pyramid: The History Of Football Tactics].

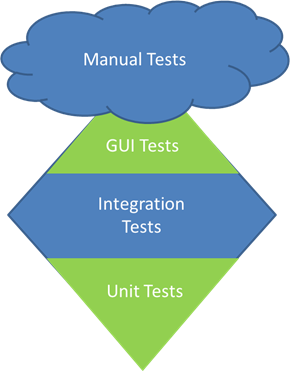

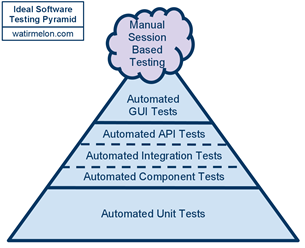

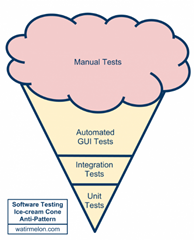

←Alister Scott takes this one step further by adding a Manual testing cloud to the top of the automation pyramid.

Now if the automation pyramid is inverted, the resulting picture is that of an ice cream cone.→

Ice cream cones might look appealing, but this is an anti-pattern for test strategy.

|

|

The Testing Diamond

A few years back I wrote up an experience report about some of the work that we did with a complex engineering application and the focus that we had on increasing overall test coverage. The team ended up with a testing model that more resembles a diamond.

They had a large developer regression suite that provides end to end integration coverage under the GUI. They also had a customer regression suite that handles much more complicated integration problems. They did not have a large GUI automation suite or a large number of unit tests. Over time the team did add more unit tests and more GUI automation, but the real value came from expanding the integration test suite. The result was a substantial reduction in defects found in beta and at ship. The strength of this middle layer is quite key and as Mike Cohn says, it is often the forgotten layer of the pyramid.

When I met up with Naresh at the 2012 Simple Design and Testing conference in Houston he told me the story of Inverting The Pyramid: The History Of Football Tactics. I had already heard about Inverting the Testing Pyramid, but had not heard of the connection to soccer. It dawned on me that in the game of soccer, the successful teams are those that are able to control the midfield.

I think it is the same way with integration tests. While it is certainly true that integration tests are more costly than unit tests, it is also true that integration is the place where the real business value is. Unit tests are often insufficient. The nature of the engineering simulation problem that we were solving is such that the solution of the whole system of equations is necessary to see the full interplay of the complex physics being simulated. Unit tests cannot easily handle issues associated with round off or approximation methods.

Pingback: Testing Rails Apps: Optimize for Business Value – The Lien Startup